|

| Diogo Morgado as Jesus in Son of God. |

The new

movie Son of God is out.

Like most other movies on this subject, Jesus is an impossibly handsome white

man—the opposite of what the real Jesus likely looked like over 2,000

years ago.

In the most recent cinematic version, by the

husband-and-wife team of Roma Downey and Mark Burnett of History Channel’s The

Bible fame, Jesus is what a Toronto Star movie critic calls a “chill” messiah,

with “great hair, a perfect pearly smile” and a “laid back bearing.”

It reminded me of a column I wrote back in 2009

about forensic research into what a typical Palestinian man in Jesus’ era might

have looked like. Spoiler alert: He doesn’t look the Jesus in the movie Son of

God.

When you think of Jesus, do you imagine him as a

muscled biker, with the word “father” tattooed on his bulging bicep?

How about as a sweat-glistened boxer, leaning on

the ropes after a successful fight?

Or maybe as a laughing bridegroom in a tuxedo,

hugging a flower girl?

Those are some of the images

that American artist Stephen Sawyer sees when he thinks of

Jesus.

|

| Jesus the boxer. |

Through his “Art for God” series, Sawyer wants

to “reflect the life and teachings of Jesus in the 21st Century.”

Of course, nobody knows what Jesus looked liked.

But we can be pretty sure he didn’t look like the Jesus in Sawyer’s paintings—a

fair-skinned white Anglo-Saxon with an angular face, long, brown hair and movie

star good looks.

Sawyer’s rendition of Jesus hearkens back

to Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ, the

famous picture of a handsome fair-skinned Jesus with the upturned gaze and long

flowing hair.

|

| Sallman's Head of Christ. |

Created by Sallman in 1924, the rendition went

on to become the best-known representation of Jesus throughout much of the last

century, gracing many a North American living room.

When many people today think of Christ, it is

that painting that comes to mind.

Both Sawyer and Sallman have it wrong—as do the makers of the new movie the Son of God.

In 2002, forensic scientists created a model of

what Jesus could have looked like, based on ancient skulls from the region near

Jerusalem where Jesus lived and preached.

Using specialized computer programs, they came

up with a model of a typical Jewish man of Jesus’ era. For eye and

hair colour, they used drawings found at various first-century archeological

sites.

The result, which was broadcast on the

2001 BBC in a show titled The Son of God, was

a man with a broad face, curly hair, a short beard and dark eyes—a typical

middle eastern man, in other words.

|

| And what Jesus might have really looked like. |

"It's not the face of

Jesus, but how he is likely to have looked given the scientific information

we've got," said Lorraine Heggessey of the BBC. "That's what people

from that area of the world looked like at that time."

In fact, the image of Jesus has been a rather

fluid thing over the centuries, reflecting the political, cultural and other

realities and imaginings of various times and places.

He was been portrayed as

emperor and ruler by the ancient Romans and Byzantines, and as a clown and

counter-culture figure in the musicals Godspell and Jesus Christ

Superstar.

|

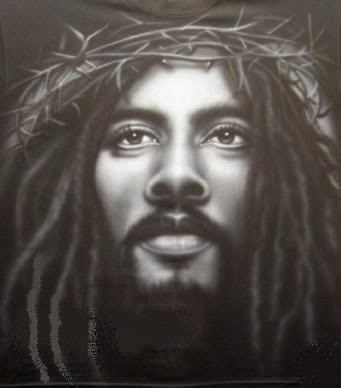

| The Black Jesus. |

African-Americans also have their own image of Jesus, and he's also been portrayed as a revolutionary or a liberator, freeing the oppressed.

|

| The Che Guevera Jesus. |

“There is a Christ for

every age," says Neil MacGregor art historian and director of the Great

Britain’s National Gallery.

For series presenter

Jeremy Bowen, the computer-generated image of Christ should look familiar to

anyone who has travelled in Palestine or Israel.

"He was a Middle Eastern

Jew. If you go to Jerusalem today, a lot of people look like that."